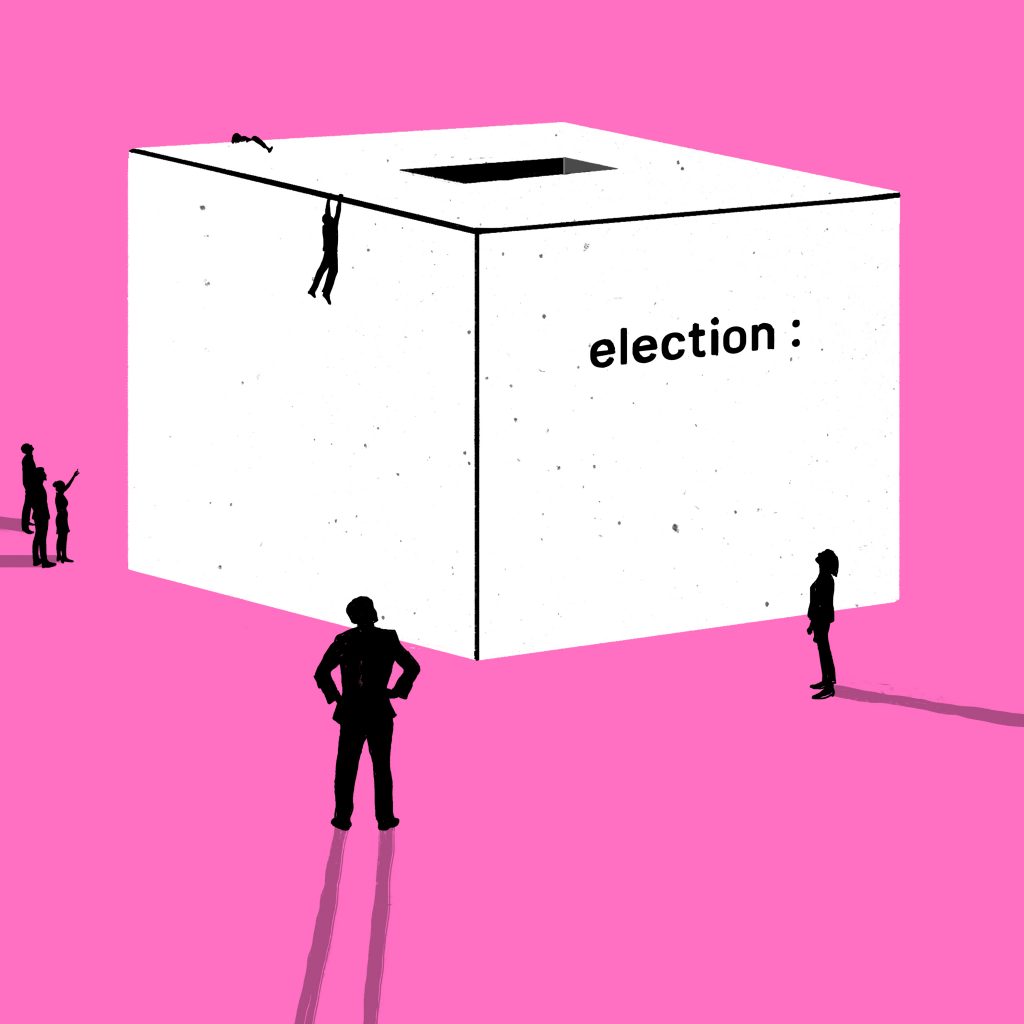

A society of solidarity and care emerging in response to state incompetence and repression enters the stage of military dictatorship at the outset of 2021. After five months of sustained peaceful protests, the number of people taking part in weekly marches is now waning as a result of poor weather, exhaustion, emigration, and pandemic spread; increasing are the networks of horizontal organization and solidarity initiatives from below. From August 2020 to January 2021, the Belarusian state and society have undergone several rapid metamorphoses: on the level of the state, a shift from state-capitalism with soft-authoritarian constitutional rule to a military dictatorship; on the level of civil society, a mass transformation of individuals into citizens and political subjects, active in a horizontal self-governance without leaders; on the level of gender relations, a crack in the hegemony of patriarchy; on the level of the protest movement, a morphing of an uprising into a revolution. If the August election presented an occasion for this process, prepared by the global context (such as the COVID pandemic and economic crisis) and local forces (such as the erosion of the welfare state and generational change), it was an event following that election that spurned this sustained protest movement. The riot police and other forces of the repressive state apparatus unleashed a wave of terror unprecedented in post-Soviet Belarus. What followed was a sustained act of defiance and resistance. A protest against fraudulent elections turned into a revolutionary resistance because in the terror actions that followed, the state authorities became identical with its repressive apparatus. It became clear that the police forces, riot police in particular, have been trained, sustained, privileged, and subsidized in the society with the sole purpose of doing exactly what they did—exercise brutality on the citizens—while fully believing themselves justified to do so, seeing themselves as the true citizens and rulers of the country. As it turned out in retrospect, protesters’ demand for the end of police violence and to hold those responsible for the crimes accountable amounted to a demand to overturn the entire system, because the system based on police violence was built in the course of the past 26 years since the democratic election of Aleksandr Lukashenko in 1994, who has retained the office of presidency since then. In other words, the Belarusian protest expressed a refusal to live in a country in which such terror is a possibility at all, which was tantamount to a revolutionary demand to remake a society as a whole.

At the time of this writing, over thirty thousand people have been detained (most on charges of violating the law on mass gatherings stipulated in Article 23.34), countless people have either left or were forced to leave the country, over 150 people are considered political prisoners, and several are dead since election day on August 9, 2020. The demands of the protesters have not changed: end police repression; release all political prisoners; hold new, fair elections. In the past five months, the protest movement has adopted neither a cohesive political program nor a geopolitical orientation. The world, and the post-Soviet sphere in particular, is following with a keen eye and a series of questions suspended in the air: Is governance without legitimacy, based solely on a repressive apparatus, possible? If so, how? Is peaceful protest insufficient for revolutionary transformation? When the times comes, will the forms of protest, characterized by solidarity, horizontality, and leaderlessness, subordinate or be subordinated by the content of oppositional politicians with the hegemonic neoliberal agenda waiting at bay? The Belarusian revolution has provided an alternative to the color revolutions in the region in the mode of its protest; will it provide an alternative in the mode of its politics? In what follows, I provide a timeline of the events, not so much from the point of view of heroes, a series of heroic actions, or sacrifices by the Belarusian civil society—of which there are many—but from the point of view of the dynamism of the protest with respect to the repression of the authorities that both suppresses and stimulates it. The meaning of these events, no doubt, is determined retroactively from the standpoint of January 2021—i.e., the events that appeared decisive from the standpoint of September have changed their meaning by January—and the current standpoint is characterized by the stalemate between the oppressive apparatus and peaceful protest. While the record of these events also serves an archival purpose, the standpoint of dynamism of the mass movement from which this story is told also serves as a reminder that any stalemate or disappearance of resistance is only apparent, so long as the causes of the resistance persist.

Before August 2020 : The presidential elections in Belarus have become somewhat of a ritual: Lukashenko receives about 80% of the votes; the opposition leader (or leaders) denounces the falsified results (though, unlike 2020, Lukashenko likely often does receive a majority of the votes) and calls for protesters to assemble in the main square of the capital; the protests are squelched within a few days or weeks and the normalcy of soft-authoritarian state-capitalism resumes, espousing elementary tenets of a welfare state, which is propped economically by subsidized Russian oil. The 2020 election, however, comes in the midst of a pandemic, on the one hand (and in the context of the botched response by the Belarusian authorities, where Lukashenko practically denied the existence of the virus), and, on the other, in the local context of economic stagnation and an eroding welfare state. The changed global conditions and their particular manifestations in Belarus fused with the contingently emerging new opposition form of leadership. Unlike the previous election cycles, typically featuring a male leader who is a pro-European politician with nationalist tendencies, the three main opposition candidates this time were different: a successful banker, a popular blogger, and a former minister. Under a pretense of juridically motivated violations, none of these three men were allowed to register as official candidates. Instead, the wife of one of the candidates, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who presented the required signatures and documentation in place of her husband, was granted the official status of a presidential candidate. This permissive gesture, no doubt, was motivated by the patriarchal attitude that dismissed the seriousness of Tsikhanouskaya’s candidacy; Lukashenko himself at the time insisted that the office of presidency would be too difficult for a fragile woman. This misogynistic attitude, inadvertently, became one of the factors in the Belarusian protest coming to be seen globally as a “revolution with a woman’s face.” The opposition united behind Tsikhanouskaya, represented by two other women: Maria Kalesnikava, a representative from the headquarters of one of the jailed candidates, and Veranika Tsapkala, the wife of the candidate forced to leave the country, who then spearheaded the presidential campaign, gathering huge crowds in major cities and regions alike.

The campaign platform of these three women was not so much a campaign for the office of presidency as it was for adherence to the current law and constitution alongside two subsequent demands: freedom for political prisoners and new, fair, and transparent elections. In effect, Tsikhanouskaya—who characterized herself as a housewife with no political ambitions, yet nonetheless proved herself a charismatic and talented politician—ran as a protest candidate. Galvanized by the presidential campaign and a number of grass-root initiatives, members of civil society registered in large numbers to serve on election committees as observers in order to safeguard the credibility of the election results. Though we will never know the exact results of this illegitimate election with certainty, by all accounts, Tsikhanouskaya gained a majority of the votes.

9 August 2020 : Election Day. Belarusian citizens go to vote in unprecedented numbers, standing in long lines to cast their votes. Official exit polls, announced after the closing of the election sites, give a decisive victory to Lukashenko, with his traditional 80%. People assemble at their polling sites to await the official result announcements. Falsifications are easy to spot; registered independent observers are refused entry. Some districts fail to post the results publicly (as required by law); in others, after posting of fraudulent numbers, there are dramatic scenes of police escorting poll workers as chants of “Shame!” are heard. By the evening, the city center of Minsk is blockaded by riot police and the special forces. The authorities block internet access for most of the country. Clashes between the police and protestors last into the night, not only in the city center but in a number of neighborhoods throughout the city. Significantly, unlike in the previous election cycles, active protests shake most major cities and the regions. Police use stun grenades, rubber bullets, water cannons, and indiscriminate violence to disperse the protestors. Medical workers report that large numbers of people are hospitalized with serious injuries.

10–11 August 2020 : Police violence continues in the days following the election. Throughout the day, riot police chase down individuals on a one-to-one basis, arresting journalists, unleashing indiscriminate terror in the cities: bystanders are hauled together with protesters into police trucks. People are afraid to leave their houses. Major internet shut-offs throughout the country continue. The street fights between protesters and police resume in the evenings. People open their apartments to the fleeing protesters to hide out until the police leave. The atmosphere of terror and uncertainty reigns. By the end of the day of August 11, more than six thousand people have been detained, more than 250 injured, and one is reported dead.

Tsikhanouskaya is forced to leave the country under threat from the Lukashenko authorities.

The true scale of violence inside the jails will only emerge in the following days. Much more than the election itself, these dramatic days of violence, unseen in the history of modern Belarus, become the event underlying the subsequent protest movement. The activation of police force at an unprecedented level demonstrates to the majority of the population that the repressive apparatus does not serve the constitution; rather, it becomes clear that for years the authorities have been training an army to attack civilians and usurp power. From this point forward, the restoration of constitutional order becomes a major popular demand, which, since the days of violence, is consonant with the removal of the system that Lukashenko and his loyalists have built up over the course of two and a half decades. Due to lost legitimacy and authority, Lukashenko’s government becomes a military junta.

12–15 August 2020 : Mass actions of solidarity commence throughout the day on August 12. Most notably, women in white—which will become the symbol of subsequent events—form human solidarity chains against police brutality. Medical workers, already strained because of the state’s failed response to the COVID pandemic, protest against the governmental actions. On August 13, workers at major government-owned factories stage strikes and walk-outs. Sites of direct democracy spring up in smaller cities, with the general public and factory workers demanding accountability from their local officials on public squares. On August 14, workers lead a march to the parliamentary building in Minsk. The numbers joining the protest continue to grow. None of these actions are formally organized or called by any political leaders; Belarus witnesses an emergence of sustained leaderless protest.

At the initiative of Tsikhanouskaya, who has meanwhile set up a residence in Vilnius, Lithuania, an organ for a peaceful transition of power under the name Coordination Council is convened, which initially includes members of cultural and political elites. Since then, all the members of the presidium of the Coordination Council have either been arrested or left the country. By January, 2021, the expanded membership of the Coordination Council has reached over five thousand, while the leadership is comprised of 50 members.

The first detained persons of the post-election days are being released from jails due to overcrowding, many of them visibly traumatized. With them, more and more accounts of police brutality, torture, and rape happening inside jails emerge. With the reports of these crimes, the popular discontent continues to grow. Police retreat, putting a temporary stop to the massive violence.

16 August 2020 : The biggest mass demonstration in Belarusian history takes place. Over a hundred thousand take to the streets in Minsk, all of them wearing white, while corresponding mass actions take place across the country; the police are nowhere to be seen. Once the sign of a nationalist movement and an official flag from 1991 to 1994, the white-red-white flag becomes the definitive symbol of the all-inclusive protest, shedding its nationalist connotations. Since this day, in part as a response to the police violence, the nature of the protest becomes consciously and insistently peaceful. A trope, dubbed “protesting Belarusian style,” emerges: people clean up after themselves and extend all possible gestures of solidarity, while restraining any attempt at violent confrontation.

Starting on this day, and continuing into the present, Sunday becomes the day of mass demonstrations, participants numbering a quarter of a million people on August 23. These weekly marches have no leaders or political speeches; their sole purpose is to occupy the streets in a sign of dissent against the political system and its supporting repressive apparatus.

Late August 2020 : Inside the factories, striking committees are being formed, while the police and bureaucrats attempt to stifle the dissent by arresting or repressing the most active members. While the initial wave of strikes helped to put an end to police violence, the government eventually succeeds at quieting down agitation in the factories. The days of late August are colored by reaction, regrouping of the regime, and the slow but insistent reappearance of police on the streets, who obstruct small-scale protest actions.

Saturday becomes a traditional day for “women’s marches,” which will continue weekly into the winter. The solidarity across civil society is growing through an expanded horizontal network of relations. Those who lost jobs on account of their political dissent are assisted in finding jobs and medical help. Neighborhoods start organizing into communities, to provide mutual aid, stage local protests as well as community events. The demands become crystalized: end police violence, release political prisoners, conduct new elections. With the authorities delegitimized, the protest assumes an increasingly republican character in its insistence on restoring lawfulness and the active participation of the citizens in political affairs on local and state levels; for the first time, many start reading the constitution and find out who their local representatives are (most of whom are typically hierarchically appointed) to voice their disapproval.

1 September 2020 : First day of classes. Protests spread to universities. Unprecedented presence of police inside universities suppressing dissent. University bureaucrats stay loyal to the Lukashenko regime: with time, most active students are expelled, prominent faculty are removed.

6–8 September 2020 : The day after the fourth massive march on September 6, Kalesnikava, the last of the trio of women who spearheaded the opposition campaign remaining in Belarus, is abducted in Minsk. When the authorities attempt to expel her from the territory of Belarus, she rips up her passport on the border with Ukraine, preventing her deportation. Subsequently, she is imprisoned on September 8 and remains in prison to this day.

September sees consistent waves of resistance and repression. Local organization continues in the neighborhoods, while the activists are jailed or forced to leave the country under acute pressure. Accredited journalists are often targeted and jailed. Two conclusions become clear in the early days of September: first, due to absolute insistence on the peaceful nature of protests, the struggle will be a prolonged one; second, the country has reached a point of no-return—whoever eventually assumes political power, nothing will be the same.

Early October 2020 : Sustained leaderless protest in heterogeneous forms continues, with weekly massive marches on Sundays and women’s marches on Saturdays as well as daily acts of dissent. October 6 marks a spontaneous march by seniors and pensioners, who proceed to take to the streets every week thereafter in the name of protecting their children and grandchildren, chanting “Fascists!” at the police who come to follow or arrest them. Tuesdays come to be the days of weekly marches by people with disabilities, that continue on into the winter. Resistance continues in the factories, without reaching mass-scale strikes. Local horizontal resistance intensifies, with street art, local evening marches, and neighborhood celebrations on a daily basis. White-red-white flags, drawings, and ribbons pop up everywhere, while government workers and police work hard to remove them. The Coordination Council launches an initiative to promote self-governance in the neighborhoods.

The Sunday march on October 11 marks the return of police violence on a mass scale. More than 700 people are arrested that day alone, but, more notably, the restraint on brutality exercised by police in the previous weeks has been abandoned. The march in the center of Minsk is followed by evening protests in local neighborhoods, denouncing the violence that took place during the day. The tension between police and the public is unstable, fluctuating between greater and lesser violence and corresponding public rebuke, which temporarily halts the violence. Police operatives exclusively wear balaclavas and masks, even in jails and during court appearances, where they use fake names, fearing retribution in their private life, by neighbors, relatives, and friends. The attempts by the government to manufacture an appearance of popular support—such as pro-government demonstrations or aggressive propaganda—largely wane: it becomes clear that its sole power rests on the endurance of masked men and the loyalty of bureaucrats.

26 October 2020 : The Coordination Council and Tsikhanouskaya announce a national ultimatum, calling on the Lukashenko regime to meet the three demands that have remained the same since the beginning of the protests. If the government fails to do so, the general strike, road blockages, and acts of civil disobedience will commence on October 26. While this call for renewed mobilization triggered one of the most massive Sunday marches on October 25, the general strike largely failed. Because of a lack of organization and a lack of coordinated economic demands—leaving the decision to strike solely to individual discretion—only a few government-owned factories were successful in triggering dissent in any organized manner. Instead, this allowed the repressive apparatus to weed out the most active dissident workers, jailing and firing them. Since the call for a general strike, the resistance in the factories has largely died down. The weeks that followed were characterized by student strikes and the solidarity actions of medical and IT workers.

12 November 2020 : In one of the most active neighborhoods, the so-called Square of Changes, Raman Bandarenka, an artist and a former member of the special forces, is beaten and abducted by masked men, likely civilians with close personal ties to Lukashenko himself, who come to remove protest symbols from the street. Bandarenka dies in the hospital the following night. Monuments and memorials spring up across the country, while masked men in civilian clothes systematically destroy them. The official television claims that Bandarenka was drunk when he was attacked, but a leaked medical report shows no alcohol in his blood; the doctor who leaked the report and the journalist who prepared its publication are still in jail to this day. Bandarenka’s last words in the neighborhood chat before he was beaten: “I am going out,” which would become a rallying cry for months to come.

15 November 2020 : Protesters gather in the Square of Changes to commemorate Bandarenka’s death. Police follow with brutal arrests, and the protesters are forced to seek cover in neighborhood apartments. The following night, police remain in the neighborhood, snatching up anybody on the streets, unless they can provide proof that they reside in this neighborhood.

Winter months : Tsikhanouskaya and the Coordination Council continue their work from abroad. The EU passes sanctions against Belarusian officials and the US adopts an “Act about Democracy in Belarus.” Tsikhanouskaya, the self-described housewife with no political ambitions, proves to be a charismatic leader recognized internationally, and easily the most popular politician in Belarus; once she reaches her goal of conducting new elections, she insists that she will not take part in them. As a sign of good will, Lukashenko proposes a constitutional reform, which is widely viewed as a delay strategy to cover his incapacity to suppress the protest movement. The strategy of the opposition is to exhaust the government economically. The scale of the economic and humanitarian crisis that will result from this stand-off is difficult to assess.

Peaceful protest delegitimized but did not topple Lukashenko’s regime before the onset of cold weather. Every Sunday still, public transportation does not run in the center of Minsk and the police block the city center in order to prevent mass demonstrations. Marches continue weekly in the neighborhoods throughout the country, organized by new emergent local communities. Daily acts of dissent do not stop. The second wave of COVID has hit Belarus, further contributing to the difficulty of successful mass action; the overcrowded jails have become a major factor in the spread of coronavirus. In response, the reaction spreads by way of the repressive apparatus. Activists are forced out of the country, and regular people are fleeing in great numbers. Criminal cases and arrests made for resistance to police reaching all the way back to the early August days of protest are working their way through the courts: two years for ripping the balaclava off a riot police officer, two years for writing “We will not forget!” on the sidewalk at the site where a protestor was killed. On December 31 at 11:34 pm—inspired by Article 23.34 of the Belarusian criminal code that was leveraged to jail most of the protestors—people across the country raise their glasses to those who languish in jails as the year changes.