One moment from August 12, 2017 that was discussed repeatedly during the course of the Sines trial was the march by members of League of the South (LOS), the Traditionalist Workers Party (TWP), and the National Socialist Movement (NSM) – groups that formed a coalition known as the Nationalist Front (NF) – from a parking garage on Market Street in Charlottesville to what was then called Emancipation Park about two blocks away (the park was previously named Lee Park and has since been renamed once again as Market Street Park). The conflict that occurred when that particular bloc of far right demonstrators clashed with counter-protesters was one of the most dramatic and widely documented events in an already tense and tragic day.

The NF bloc clearly came prepared to fight: many members of LOS and TWP wore helmets and carried uniform police riot shields. A number of them also had flagpoles that quickly became weapons (a practice that was frequently discussed on message boards beforehand). That day in Charlottesville, there were also antifascists who brought helmets, shields, and sometimes flagpoles, but as the NF members approached the park, they were confronted by a line of people who were simply locking arms with little to nothing to protect them. This fact makes the footage of that moment all the more gut-wrenching to watch. Ultimately, the NF groups all made their way into the park.

Passing, Then and Now

For supporters of the TWP and its leader Matthew Heimbach, there could be little doubt that that moment had to be immortalized in meme form. And so the day after the rally that left one dead and at least nineteen injured due to a car attack, TWP member “Commander” Derrick Davis took to Twitter to write “In memory of plowing through a human wall of communists.” Appended to that comment was a photo of Heimbach (with Davis in the background) emblazoned with the phrase “We Have Passed and We Shall Pass Again.”

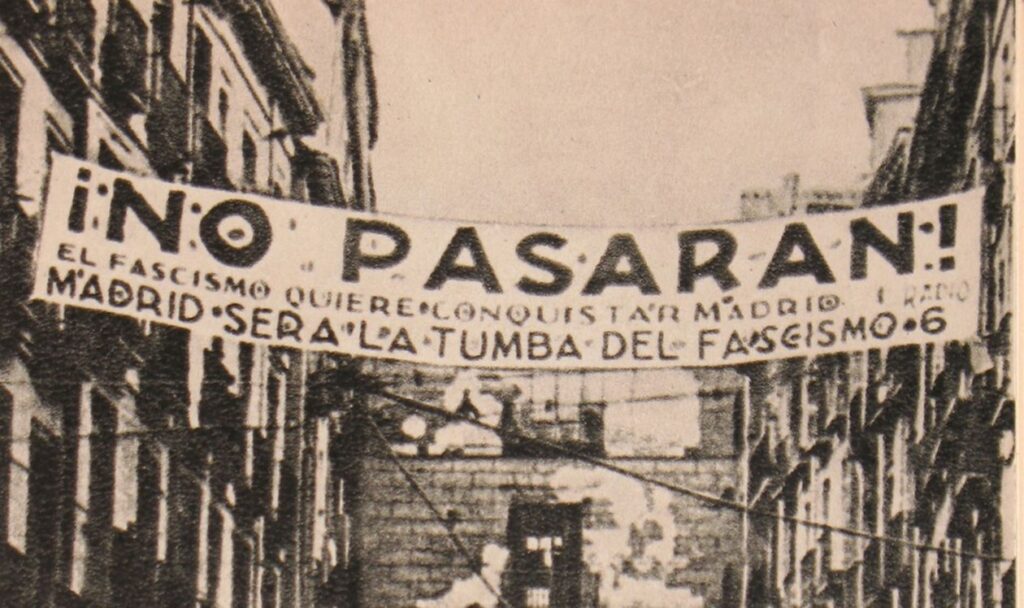

Heimbach was questioned about that meme during the Sines trial and denied that it alluded to any intent to commit violence. On the contrary, he argued that antifascists “routinely chant ‘no pasarán’” when confronting far right actors and that anyone in his organization would have understood the reference. Although the slogan no pasarán (they shall not pass) was previously used by French soldiers during World War I (on ne passe pas), today it is indelibly linked to the Spanish republican cause during the 1936-39 civil war. Even in Spain, however, that was not always the case. It initially appeared on right wing posters in Madrid in 1936 in opposition to the newly elected Popular Front coalition. It was then reclaimed by Spanish Communist Party leader Dolores Ibárruri during a short, impassioned, unscripted speech she gave during a radio broadcast on July 18, the day after the war started.

After that, it rapidly became an international antifascist slogan (generally expressed in Spanish, even among non-Spanish speakers) and remains popular to this day. Because it is so iconically linked with antifascist militancy, Heimbach asserted at trial that the proper response is sí, pasaron (yes, they passed).* All of this makes “We have passed and we shall pass again” a kind of implicit translation of a Spanish phrase that is not nearly as widely used as no pasarán, yet just as recognizable to Heimbach’s constituency: as he noted under questioning by the Sines plaintiffs’ lawyers, anyone closely involved with the white nationalist movement would have understood the reference.

While Madrid promised to be “the tomb of fascism” in 1936, that promise went tragically unfulfilled. In 2017, the phrase “we have passed” had the effect of asserting continuity with historical iterations of fascism (notwithstanding the continued debate as to whether or not the Franco regime should properly be regarded as fascist) or inserting their organization into a larger historical narrative. Spanish nationalists did, indeed, forcibly enter Madrid just as Heimbach and his organization forcibly entered a park. The comparison is self-aggrandizing and obscene, but that is par for the course in the language of the alt-right.

Borrowed Buzzwords

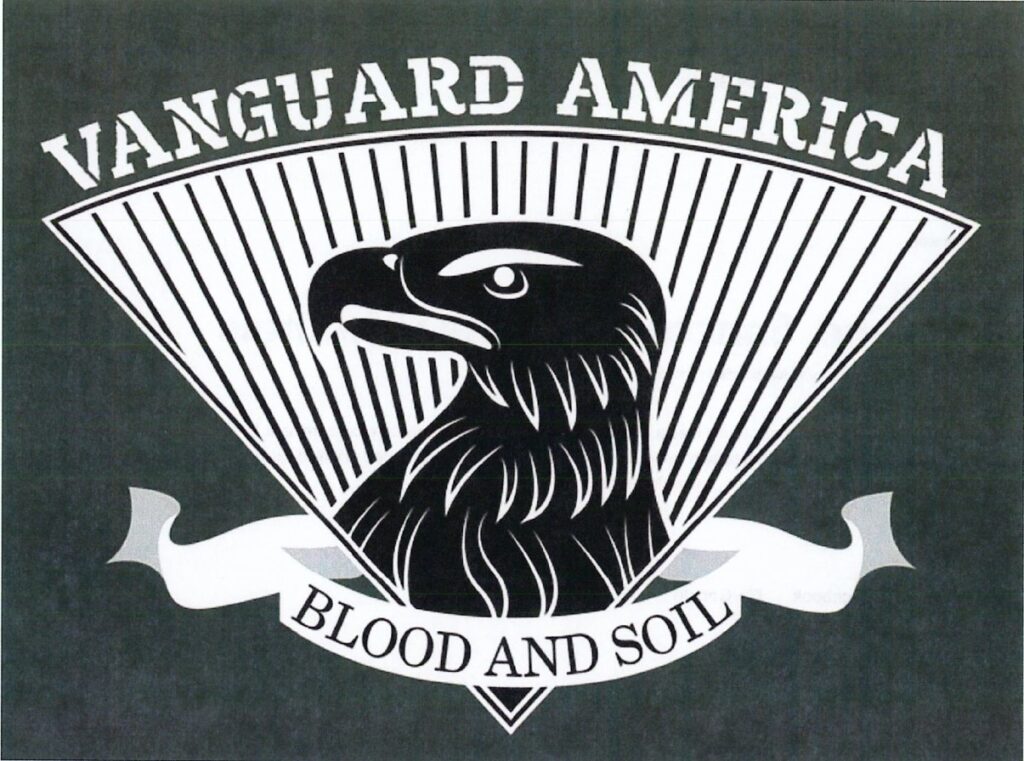

Borrowing historical slogans from languages other than English – sometimes translated, sometimes not – is a well worn linguistic feature of twenty-first century white nationalism in the US. Particularly salient in discussions of Unite the Right is the phrase “blood and soil,” chanted by participants in the tiki torch march on the University of Virginia campus on August 11, 2017. Its provenance and usage under the Nazi regime are a complicated matter, but suffice to say that it is most commonly associated with the 1930 book Neuadel aus Blut und Boden (A New Nobility of Blood and Soil, recently published in English for the first time by a neo-Nazi press) and its author Richard Walther Darré, the Nazi-era Minister of Food and Agriculture. Under his leadership, Blut und Boden became the ministry’s motto. The slogan was also used to rationalize Nazi claims to land where German populations had settled outside Germany, thereby justifying expansionist/irredentist military adventures.

There is little to indicate that the torch-bearing fascists of August 2017 were especially interested in the specifically rural, agrarian context in which “blood and soil” was most frequently invoked under Hitler’s rule, however a connection with the Nazi era has its own inherent appeal within the white nationalist movement. Moreover, the notion that land belongs to those who have bled and died on it (wherein “blood” is granted metaphysical significance) is perfectly in line with movement ideology: adherents generally believe that the United States was founded by elite, revolutionary white men who risked and sometimes lost their lives to bequeath their new country to their own descendants. By their reasoning, the land within present-day US borders therefore does and should still belong exclusively to white people (despite the vast accumulation of contradictions in the logic behind that belief).

“Blood and soil” was not a slogan that Unite the Right participants discovered only upon arriving in Charlottesville. It had enough currency to not only be used in the URL of the website run by Sines defendant Vanguard America (now defunct), but to also be worth stealing when member Thomas Rousseau locked other group leaders out of the site and rebranded the organization as Patriot Front. Patriot Front still periodically marches through cities throughout the US chanting “blood and soil!”

Other jargon borrowed from the Nazi era abounds among Sines defendants. Neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer took its name from the Nazi tabloid Der Stürmer. It regularly featured crassly antisemitic cartoons and racist “humor,” a tradition that The Daily Stormer has eagerly taken up.

The Traditionalist Workers Party adopted the slogan “Faith, Family, Folk,” which, whether intended or not, is clearly redolent of the expression Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church). The latter was used at least as far back as the late stages of the German Empire to delineate the acceptable parameters of women’s activity and was taken up again under Nazi rule to push back against more progressive attitudes that had developed during the Weimar era.

Moreover, English-speaking neo-Nazis regularly use the word “folk” as a substitute for “race” or “ethnicity.” Here again, borrowing from German has its own appeal: the word Volk is an embattled term that has had racial connotations in some contexts at least since the rise of Germany’s ethno-nationalist völkisch movement in the 19th century, but it also sometimes refers simply to “the people.” The slogan Wir sind das Volk! (We are the Volk!), for instance, was used in protests against the East German government during its final years to delineate between common citizens and the ruling party elite. More recently, that slogan has been recuperated by far-right, anti-immigrant demonstrators in contemporary Germany to delineate between “ethnic” Germans and Others, who, we can assume, are to be perpetually excluded from authentic Germanness.

White nationalism is defined in part by an urge to maintain strict boundaries between often arbitrarily defined populations, yet it is remarkably amenable to blurring linguistic lines. The exact parameters of acceptable borrowing are subject to change, but they frequently express a desire for continuity with historical movements and events that are deemed worthy. That gaze toward the past, in turn, says a lot about their ambitions for the future.

* It is impossible to be certain whether Heimbach did, in fact, mean pasaron (“they passed”) or pasarán (“they shall pass”) due to the fact that he pronounced the latter “puh-SAH-run” and, if he ever meant to say the former, he pronounced it the same way. I am assuming he meant pasaron here because it is in keeping with the text in the meme, although the most likely conclusion is that he just doesn’t think much about Spanish grammar and doesn’t particularly care. Whatever the case may be, I think we can take this as evidence that he has not, in fact, heard antifascists “routinely chant” no pasarán.