by Farzad Kamangar

Translated from the Farsi by Tyler Fisher and Haidar Khezri

[view as .pdf]

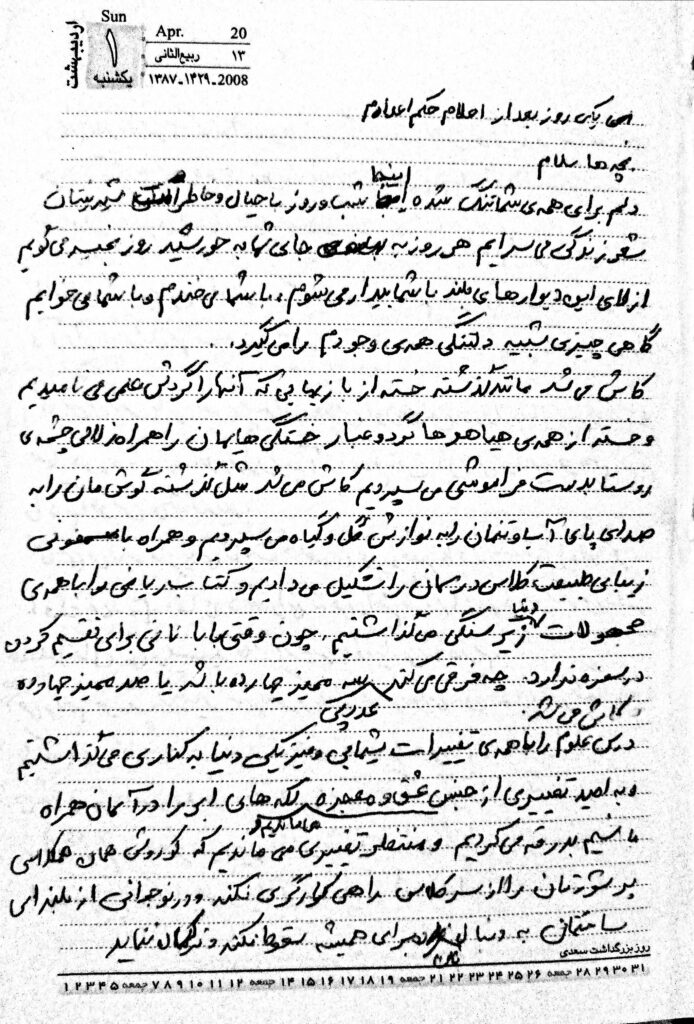

A day after the decree of execution

Hello, Class.

My heart constricts from missing every one of you. Here in prison I compose the poem of life’s eternal song, day and night, with sweet recollections and dreams of you. Every morning, in your stead, I greet the sun. I wake up alongside you within these high walls and laugh with you and sleep by your side. Sometimes, something like the tightness of heartache overwhelms me with longing.

I wish we could release the dust of our day’s weariness to the village spring’s crystal-clear hands of forgetfulness, like in the old times when we returned, exhausted from all the excitement of our games in the fields (an “official school field trip,” we called it, of course).

I wish we could, as in old times, surrender our ears to the “Footsteps of Water,”1 and our bodies to the caress of flowers and grass, and start our class with nature’s beautiful rural symphony, and put our math book under a stone with all the world’s unknowns still to solve, because when a father can Add no Bread to his Children’s table—the most basic ABCs, rudimentary math—what difference does it make if pi equals 3.14 or 100.14? And I wish we could set aside the science lesson about all of the world’s chemical and physical changes, and contemplate changes in matters of love and miracles, and study the breezes and convoys of clouds, awaiting a change that would avoid sending your lively little classmate Kurush straight from the classroom to the construction site, and, as a teenager, keep him from tumbling off a building in search of bread and leaving us forever—instead, a change like that of the New Year, bringing everyone a new pair of shoes, a set of fine clothes, and a basket brimming with candies.

I wish we could again furtively practice our Kurdish alphabet, far from the principal’s stern eye, and compose poems for each other in our mother tongue, and sing and dance hand in hand, and dance and dance.

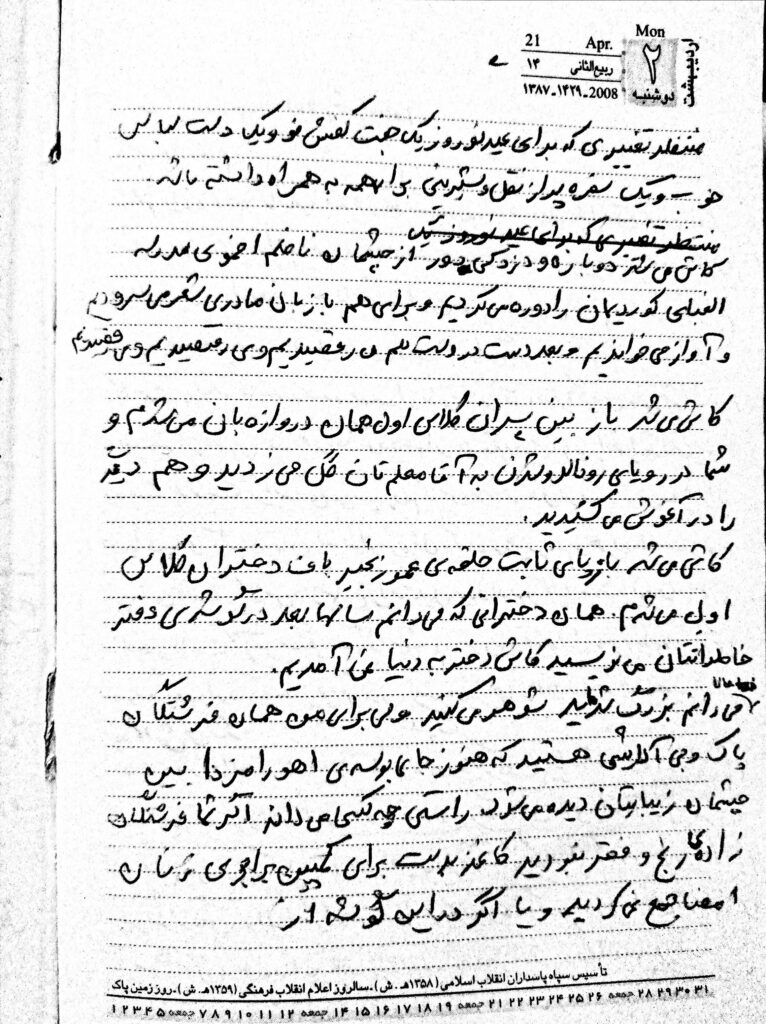

I wish I could again be goalkeeper for the first-grade boys, and you will score goals against your teacher with the dream of becoming Ronaldo, with hugs to celebrate every goal. Ah, but sadly, in our land, dreams and wishes gather the dust of forgetting even before it settles on picture frames.2 I wish I could again join in the “Ring-around-the-Uncle” game, leading the chants of the first-grade girls, you girls who, years later, at the corner of a page in your diary will write: “I wish I wasn’t born a girl.”

Now I know you have grown up and will marry. But for me, you’re the same pure and graceful angels with traces of Ahura Mazda’s3 divine kiss still clear between your beautiful eyes. And really, who knows, if only you angels were not children of poverty and sorrow, you wouldn’t have to go everywhere, paper in hand, collecting signatures to support women’s campaigns for equality. And if you had not been born in this godforsaken corner of the earth, you would not be forced to bid farewell to school for the last time at age thirteen, with eyes full of tears and regret, under the white veil of becoming a woman, and would not experience, with every fiber of your being, the bitter story of the second-class gender.

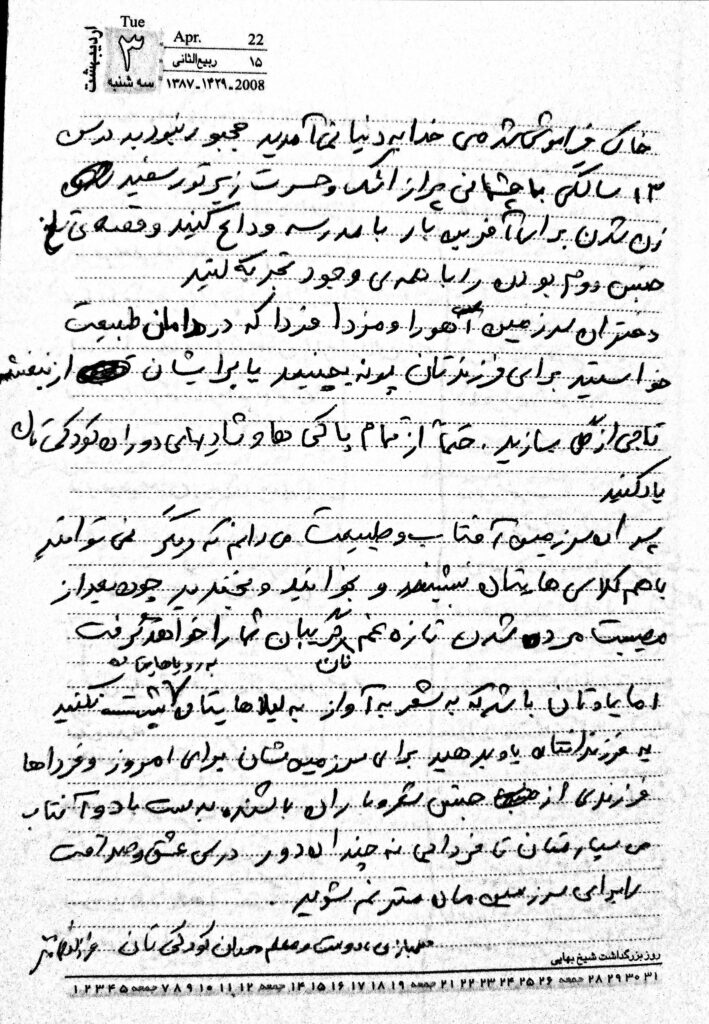

You daughters of the land of Ahura Mazda, tomorrow when, in the folds of nature’s skirt, you pick minty pennyroyal leaves for your children or weave a flower-crown of violets for them, remember to recite all your childhood innocence and joys.

You sons of the land of nature and the Sun, I know you are no longer able to sit with your classmates, to read and laugh, because right after the tragedy of becoming a man, the grief of earning your daily bread will seize you by the collar. But remember not to turn your back on poetry, on song, on your lovers and your shared dreams. Teach your children to be heirs of poetry and rain, for their homeland, for their todays and their tomorrows.

I entrust you to the hands of the wind and sun. Until that not-so-distant tomorrow, recite the lessons of honesty and love for our homeland.

Your friend, companion at play, and childhood teacher,

Farzad Kamangar

Rajai-Shahr Prison of Karaj

28 February 2008

translators’ note: Farzad Kamangar was a Kurdish primary school teacher, poet, journalist, and human rights activist who was executed, age thirty-five, along with four other political prisoners on May 9, 2010, in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. Kamangar was born in the city of Kamyaran, in the Kurdistan Province of western Iran. As a Kurd, he advocated for greater cultural and political self-determination for his minority community, and his advocacy extended to environmentalist causes, women’s rights, and educational reforms. His writing, for periodicals published by Kamyaran’s Department of Education and by a regional human rights organization, displays his dual commitment to beautiful literary expression and unflinching documentation of human rights abuses in Iranian Kurdistan.

In July 2006, Kamangar was arrested in Tehran while accompanying his brother for medical treatments. After years of imprisonment and torture, Kamangar was sentenced to death on charges of Moharebeh (waging war against God) and undermining national security. The Iranian Islamic regime’s application of the term Moharebeh to Kamangar’s case follows a pattern of recurring historical oppression because it has been applied to Iranian Kurds since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Iran has invoked this “crime” as grounds for executing political prisoners in 1988, condoning the Serial Murders of Iran (1988–1998), cracking down on the presidential election protests in 2009, and suppressing the current “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. As a non-Shi’a Kurd, Kamangar was especially vulnerable to this charge as a minority by religious sect, ethnicity, and language.

Just days after receiving the death sentence, Kamangar penned, in Persian, the letter we have here translated into English. This letter is the first of several he wrote to his students immediately following the decree of execution. He managed to smuggle the letters out of prison, one by one, when members of his family visited. These letters, which express Kamangar’s unbounded love for his students and for his Kurdish homeland, survive as a vivid testimony of his unquenchable spirit. Of particular note is Kamangar’s sensitivity to how forces of socioeconomic class and gender would inevitably shape his students’ lives, in a context wherein girls typically leave school at the age of ten or eleven and marry young into a restrictive domestic radius. Boys, for their part, tend to spend more years in school and enjoy greater social freedoms, yet face the high incidence of industrial accidents and exploitative manual labor for subsistence. Kamangar recognized the Kurdish struggle against intersecting factors of oppression yet expressed an indomitable hope for the Kurds’ future.

The brutal conditions of Kamangar’s imprisonment, the physical and mental torture to which he was subjected, and his execution brought global condemnations of the Islamic regime of Iran from many organizations, including UNICEF, Education International, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch. Protests have marked the anniversary of his execution in Paris, London, Berlin, Washington, D.C., and many Kurdish cities.

The legacy of Kamangar’s resistance and struggle for justice, in the face of the atrocities of his imprisonment and execution, has reverberated in Kurdish literature. Shêrko Bêkes (1940–2013), the renowned Kurdish poet, wrote an elegy for Kamangar, titled “Republic of Execution” with reference to the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Kurdish Iranian director Bahman Ghobadi dedicated his film Rhino Season (2012) to Farzad Kamangar and Sanea Jaleh (1985–2011), a Kurdish student who was shot dead in the protests that marked the Iranian Green Movement. In 2020, Ava Homa, the Kurdish writer, journalist, and activist, dedicated her novel, Daughters of Smoke and Fire, to “Farzad Kamangar for imagining otherwise.” His letters from prison invite his readers to imagine higher possibilities, higher ideals beyond the Islamofascism that sought to obliterate his native language and liberties. As Iran’s authoritarian regime yoked the forces of theocratic fanaticism and the nation-state in the service of a Persian and Shi’a Islamic Republic, exclusive of and discriminatory towards ethno-racial and religious minorities, Kamangar counters with a primary school teacher’s mild-mannered defiance and irrepressible dreams.

Kamangar’s letter to his students, which has not been previously translated into English in full, is as much a prose poem as a letter. Its poetic qualities repeatedly remind the reader that this is no ordinary letter. Parallelism and repetition (anaphora and alliteration), together with an onrushing polysyndeton, convey an outpouring of memories and reverie, channeled within his careful artistry and the epistolary form. He expresses a confluence of soaring ideals and winsome whimsy alongside the ordeals of political imprisonment, ethnic repression, and social inequities. Our translation sought to preserve the letter’s stylistic and thematic interplay. We have kept domestication to a minimum, especially when the letter evokes an excursion into the Kurdish countryside with young students. The Persian children’s circle game, Amoo Zanjir Baf (literally, “Chain-Weaver Uncle”), for instance, is lightly modified to “Ring-around-the-Uncle,” recognizable yet recognizably distinct.

FARZAD KAMANGAR, a Kurdish school teacher, poet, and activist, was imprisoned and tortured by the Islamic Republic of Iran for four years. In prison, even after being sentenced to death, Kamangar continued to advocate for human rights and justice for Iran’s minority communities in letters that he smuggled out of prison, sometimes in fragments, addressed to his young students and other political prisoners. The Islamic regime executed Kamangar at age thirty-five in 2010.

TYLER FISHER completed his doctorate in Medieval and Modern Languages at Magdalen College, University of Oxford. He is now an Associate Professor in the University of Central Florida’s Department of Modern Languages and Literatures. His book-length translations of poetry include José Martí’s Ismaelillo (Wings Press 2007) and Federico García Lorca’s The Dialogue of Two Snails (Penguin 2018), and he has also published translations of poetry from Catalan, Kurdish, and Aramaic.

HAIDAR KHERZI completed his doctorate in Middle Eastern Comparative Literature at Damascus University. He also gained ACTFL/ILR OPI certifications for Persian/Farsi and Kurdish (2017), and for Arabic (2021) from the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. He designed and developed the first and only Central/Sorani Kurdish curriculum for North American universities under a Title VI U.S. Department of Education Grant, and through Indiana University’s Center for the Study of the Middle East. In 2019, he became the University of Central Florida’s first Assistant Professor of Arabic, a key role for building the university’s capacity to teach Middle Eastern languages and cultures. Khezri is the author of Comparative Literature in Iran and the Arab World, 1903–2012 (Tehran: Samt Press, 2013; second edition, Cairo: Egyptian Cultural Academy, 2017) and It Is Only Sound That Remains (Erbil: Salahadin University Press, 2016). He is currently working on a book-length project about the reception of Franz Kafka in Middle Eastern literary cultures.

Together, Fisher and Khezri have published collaborative translations of Kurdish poetry in The Bangalore Review, The Brooklyn Rail, Y’alla, and Poet Lore, as well as in the anthologies My Moon Is the Only Moon: The Poetry of Nali and Essential Voices: Poetry of Iran and Its Diaspora.

- A poem by the renowned Iranian poet and painter, Sohrab Sepehri (1928–1980).

- This sentence does not appear in the manuscript letter but does appear in the printed version, a difference which reflects the difficulties Kamangar and his relatives faced when smuggling these messages out of prison in written fragments, via transcriptions from phone calls, and other means.

- In Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda is the supreme beneficent god, creator of the universe.