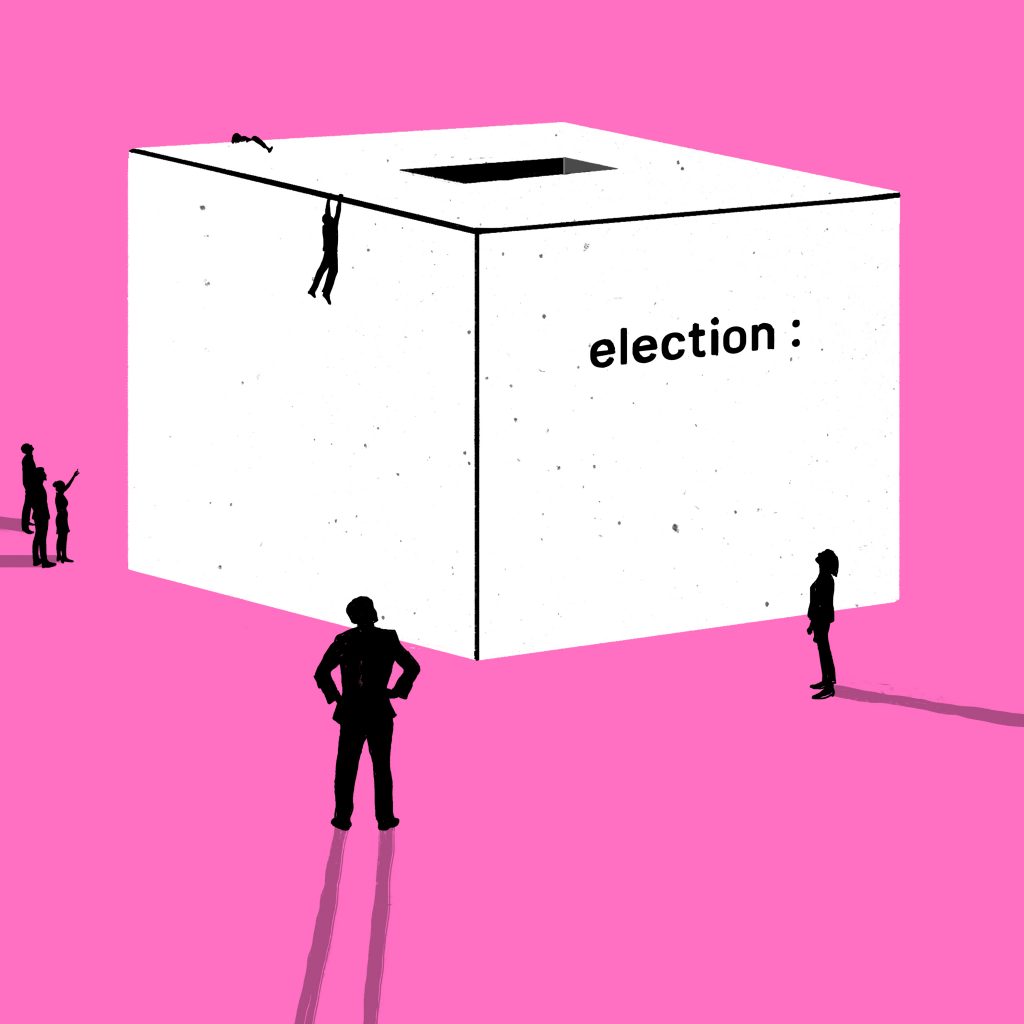

In 1998, the Green Party in Germany ran an election campaign with the slogan “New majorities only with us.” But what kind of majorities can elections create? I might be asking the obvious, given that elections are decided by majority votes channeled through an elaborate system of representatives. The elections in Germany in 1998 provide a case to complicate this notion of political and consequently national majority, because the Green Party and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) campaigned by centering social justice and by addressing the politically marginalized and ethnic minority segments of the populace, specifically German-Turks. A new political majority was constituted in 1998, and old convictions of an ethnically homogeneous nation were challenged through several statements, policies, and ultimately legal reforms. The figure of the foreigner (Ausländer) was deployed productively by all parties and ultimately facilitated the shift into a new national self-conception within a neoliberal Europe. In fact, I think, more than “new majorities,” a new minority emerged in the years after the 1998 elections—a Muslim minority. And for this minority to emerge and remain productive for political purposes, a longer history of migration built on the logic of return had to be undone.

How so? Let me explain through a personal-political account of ever-shifting Turkish life in Germany.

In the 1998 German federal parliamentary elections, the SPD won with a 51.6% majority against the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). In the early years of his tenure, Helmut Kohl, the CDU chancellor from 1982–1998, had symbolized economic stability, a peaceful reunification of the two Germanies, and a restrictive migration politics marked by his 16-year-long mantra that “Germany is not a country of immigration”—thus leaving the ca. 2.5 million guest worker families from Turkey in an exceptional state of social and political toleration (Meier-Braun 2002). Guest workers—a predominantly male work-force on temporary work and resident contracts—had begun arriving in Germany since the mid-1950s, first from Greece, the Balkans, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Turkish guest workers started coming in 1961 after a bilateral agreement had been signed between Germany and Turkey (Chin 2007). And despite the stop in labor recruitment in 1973, the number of Turkish migrants kept growing, because they opted to bringing their families to Germany instead of leaving secure jobs.

This communal growth shifted the fact of Turkish presence in Germany from a functional one, as the manpower necessary to fuel the German economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder), to a social one, with entire families entering public and social spaces such as schools, parks, the national health care system, and social housing. Guest worker children, in contrast to their working parents, were an open annoyance with no use for the German economy. In agreement with the Turkish state, Turkish children were to receive additional “mother-language courses” so that they would remain fit enough to be reintegrated into Turkish schools, once they returned to Turkey (Van Wyck 2017). The city of West Berlin even went so far as to institutionalize segregated “Turk classes” (Türkenklassen) in some schools, in order to ensure full education in Turkish, as agreed upon and coordinated with the Turkish state for the future returnees (Demir and Sönmez 1999). In the years after 1990, questions arose as to whether Helmut Kohl and his party politics were still in sync with the new reality that German reunification had caused. In order to integrate Germans from the former East Germany, and even ethnic Germans from former Soviet member states, into the newly reunified German economy, German factories and employees fired or released Turkish workers with financial compensation and replaced them with their newly arrived compatriots. But Turks were not leaving Germany, even though they felt that “the Berlin Wall had come falling down on their heads” (Çil 2007).

I grew up in this Germany, where Turkish fathers came back from their manual labor workplaces exhausted and sweaty. My father’s retirement in the early 1990s marked the end of the guest worker era for me. I also had to go to mother-language courses once a week for 3 hours. And although my generation’s lived everyday reality was navigated bilingually and oftentimes in a hybrid manner (Yasemin Yildiz 2011), the neat institutional categorization of these languages made me see the rest of my regular instruction as a kind of stepmother-language school. In a way, this categorization was affectively prescriptive and corresponded with how I was treated there. Once during schoolwork in elementary school, my teacher tapped on my shoulder and asked if my family and I had plans to go back to Turkey. She was just curious, she added. Instead of returning, I saw people changing and reinventing how and where they worked and who they were. I saw the fathers and brothers of Turkish friends changing from factory workers into entrepreneurs, mostly in the restaurant business selling döner kebab. And while East Germans settled in the regions of former West Germany, Turkish guest workers ventured into the former East to find ideal locations to open more Turkish restaurants that would appeal to their new clientele.

The Turkish restaurant owner and the East German patron were in a symbiotic relationship, they needed each other to enter these roles as restaurant owner and restaurant guest (see also Shoshan 2016). Most of these restaurants were opened in rather smallish towns, first in order to rule out other international competition from Vietnamese, Greek, or Italian immigrants. Second, most of these towns did not usually have “international restaurants” in the way they had developed in Western Germany since the 1980s (Voigt 2017). Western Germans used “Italian,” “Greek,” and, after the 1990s, “Turk” as a shorthand to refer to their restaurant of choice. I doubt that East Germans used the same shorthand—which comes with an air of entitlement and condescension often ascribed to the “Wessi” (West German) by East Germans, who are in turn named “Ossi,” which comes also with a set of fixed ascriptions. But I wonder whether the figure of the foreigner, who was in a subordinated relationship to the Wessi, became a provocation in East Germany because he was present there as a self-made man, one who had figured out German capitalism in its various formations and adapted to it, as a “protean homo economicus” (Brown 2017). And here was the East German, who had just had his whole world dismantled in order to be brought into the kind of freedom that his liberal brother had to offer—as the systematic separation of the Germanies during the Cold War has been described in kinship terms (Borneman 1992)—watching as the blood and kinship ties on which he thought he could rely were not aiding him in competition with these “foreign” entrepreneurs. In a way, East Germans resembled Turks in the way that their place depended on the grand utopias of West German politics. But Turks did not have the same brotherly illusions about their place as East Germans had (see also Foroutan & Hensel 2020).

The 1998 election, however, gave birth to an illusion of belonging, not qua blood ties but qua birthright, as the SPD embraced migration during their campaign as an essential part of Germany’s social make-up. While Turks had already started naturalizing in large numbers in the early 1990s, the prospect of birthright citizenship and a governing party that would acknowledge Turks as legitimately present and belonging gave the election a whole new promise of resetting things. The Turkish vote certainly went to the SPD and the Greens in 1998. The reality of Turkish migration as one of permanence called into question what the CDU had been promising all these years: Turks leaving Germany. But Turkish guest workers, similar to other guest workers before them, were here to stay. And although the figure of the foreigner and the Turk were conflated and used interchangeably, the foreigner included people from Morocco to Vietnam, from Bosnia to Somalia as well. In this sense, Turks had a central role in bridging several positions in the German political landscape. As guest workers, their presence was defined as one of temporary import, tied to limited work and residence permits. As foreigners, they were different from other guest workers from Southern Europe, because the latter were now considered part of a greater European family; and since Turkey’s membership in the European Community was not yet confirmed, Turks resembled non-European foreigners even more strongly. The category of the foreigner included refugees from former Yugoslavia, Iraq, and Afghanistan, their permanent stay in Germany uncertain and subject to contested asylum laws. The resemblance was deadly: asylum shelters and private homes of Turkish families became targets of right-wing neo-Nazi arson attacks.

In a country that congratulated itself on a peaceful revolution, people were burnt alive for being foreigners. The towns of Mölln (1992), Rostock (1992), and Solingen (1993) became infamous for arson attacks that took the lives of innocent children and their parents, while up to hundreds of people stood by clapping gleefully at the sight of burning buildings. I remember coffins wrapped in Turkish flags and Turkish politicians claiming the bodies of their burnt compatriots, meanwhile not a single high-ranking German politician on the scene. Never will I forget the charcoaled house of a Turkish family with a gigantic Turkish flag hanging on its façade. The surviving grandmother, Mevlüde Genç, a pious veiled Muslim woman in her later 40s who had just lost five family members in the fire, was brought into public to speak of her pain. On a prime-time late-night TV show, Genç was asked how she felt about those who took away her loved ones. Speaking in Turkish, she responded that she forgave them. The moderator asked if she did not feel anger towards them, a tiny bit. She responded that she prays for them, as she prays for her dead children to be in heaven with God, adding that she grew up seeking the blessings of her elders, as well as their prayers and to excel in good deeds. In the intimate space of our own living room, my family and I were glued to the TV and were able hear Genç speak in her regional dialect as a traditional Muslim woman. The German synchronous translation was more sanitized. She sounded like a female Jesus to me, as I did not know this kind of language in German outside of the Church. To me as a child, Germans did not speak like this; they spoke the language of liability, insurance, and police. But Genç did not speak legalese but the language of forgiveness.

In public and media, these deadly incidents were treated as shameful exceptions, as remnants from a previous time. German-Jewish figures and communities were the first ones to understand the signs of racial hatred (Mandel 2008). Well-meaning liberal-minded Germans took to the streets to show solidarity with the foreigners, but no one questioned that perhaps the very term “foreigner” was what set those people up as targets. In retrospect I am able to see that this heterogeneous population from Turkey labored as guest workers, lived as foreigners, and died as Turks. Or, put differently: their labor was claimed by Germany, their life was claimed by German society, and their death was claimed by Turkey. In leaning into their traditional upbringing and faith, they could bear such atrocities and project a life into death here and thereafter. But what was theirs to claim in a country in which their presence was mobilized for a politics of immigration denial?

The election of 1998 changed the possibility for Turkish claim-making in stark terms. With the change in government from the CDU to the SPD/Green Party coalition, the Berlin Republic—as post-reunification Germany came to be called—acknowledged for the first time that Germany was a country of immigration by virtue of its social reality. A reformed citizenship law effective starting January 1, 2000, allowed for conditional birthright of German-born children to migrant parents as long as one parent had been a legal resident for 8 years and permanently employed. This right remained further conditional upon the parents’ active claim to German citizenship for their newborn. Still, the German-Turk came officially into existence, and while this could also mean that she may or may not be a German citizen, she was nevertheless officially, permanently at home in Germany. But the change in citizenship law came at a high price. It was not enough to be decades in Germany, German-born, German-(higher)educated, and a German citizen, one needed to conduct oneself in specific ways by publicly disavowing traditional communalism and embracing Germany as it conceived of itself as a tolerant and open (weltoffen) liberal democracy. And although the organized neo-Nazi murders of Turks, specifically restaurant owners, did not stop during the SPD/Green Party government, the possibility of such racist crimes was denied and only by mere coincidence was it discovered that a neo-Nazi group called National Socialist Underground (NSU) was targeting Turkish restaurant owners. The police as well as political discourse ascribed these “döner murders” to a Turkish clan mentality, as macabre evidence that Turks have not yet really “arrived” in Germany (Schminke & Siri 2014).

The labor market was at the same time also reformed by a neoliberal logic—a logic officially enshrined in ongoing entrepreneurship and risk-taking, in reduced permanent employment, in shrinking unemployment benefits and social welfare, all of which were a part of a new labor policy. All these changes happened at the same time that the German Left was mainstreamed into institutions of power and began mobilizing notions of Europe after the Holocaust and international human rights (Slobodian 2018). These market-oriented reforms were introduced in 2002 and intersected with the security concerns following on 9/11. Being Turkish acquired a new quality in those years, one that could not be mitigated with a German passport, which the election of 1998 had placed within reach.

The political opening of 1998 was then quickly curtailed by security concerns emerging in various domains, including public education, immigration, and the labor market. Senator of Finance for the State of Berlin, Thilo Sarrazin, claimed that Germany and specifically Berlin was in economic hardship because of foreigners who sucked dry the welfare system. He went on to write several books about the racial make-up of Muslims and how laziness was genetically heritable and reproduced in cultural life. This logic insisted on explaining the concentrated number of Turks in certain neighborhoods, high drop-out rates from schools, lack of higher education, the crime rates, and the ills of multiculturalism generally (Shooman 2014). The figure of the foreigner lent itself to the realization of a neoliberal governance, designed to awaken the foreigner from his multicultural slumber while overhauling the entire economic system that had been built through his labor. As if there had been any systematic multicultural politics, conservative politicians now declared multiculturalism a lost cause. Turkish migration to Germany had been predicated on the denial of a permanent political and social presence. Relatedly, a bilateral politics of return had produced a social reality of impasses. Nowhere was this migration history fully recorded and given institutional weight for further serious inquiry. Instead Turks and many other Middle Eastern migrants were discussed as still being “in transit” (Göktürk, Gramling and Kaes 2007). And now, after 9/11, this same politics was harnessed to speak of Islam and the threat of Muslims. The terms Ossi and Wessi disappeared from public usage and a new ethnic German majority took shape vis-à-vis Muslims as a racialized-religious minority.

The Muslim did not simply replace the foreign Turk, however (Schiffauer 2006). In 2006, the CDU won back the government after a vote of no-confidence removed the reigning SPD/Green coalition from power. The recently minted figure of the Muslim—from now on closely governed through regulatory and disciplinary policies initiated by the German Islam Conference (DIK)—transmuted the foreigner into new a legal security regime, which warned of the danger of unsecularized traditional Islam spilling into German secular politics (Amir-Moazami 2011). Instead of becoming part of the promised new majorities in 1998, Turks were reassembled as part of a new homogenized religious minority whose historical formations are not accounted for in the way it shaped up relationally through these various political shifts (Partridge 2012). Now, being Turkish meant having transnational ties to the Middle East and to other Muslims in an entity imagined as “the Muslim World” (Aydin 2019), an entity detrimentally opposed to “the Christian image of man,” which was also the image of free universal mankind as such (Meier-Braun 2002). Is it a surprise that German-Turkish director Fatih Akin produced a feature film inspired by the NSU murders, replacing the actual grieving family members of 10 Turkish men with one white US-American actress in the role of the innocent German wife (Akin et al. 2018)? Was Turkish grief too particular, too Muslim, and ultimately “un-German” (El-Tayeb 2016) enough to be legible to a wider audience? Or was Turkish death just cheap, because now it was essentially Muslim death, always already closer to a deserved death than a merited good life?

During fieldwork in Berlin, I witnessed how veiled Muslim women, who were thought to lack the appropriate attitude for work on the open labor market, could be deployed for administrative work in the shadows, way below minimum wage. It became clear to me then that these women were not outside of a market logic, they were in fact the necessary engine, providing underpaid labor comparable with other multicultural contexts (Korteweg 2017). My own attempt to critically engage this transformation of former migrants and refugees into Muslims has placed me squarely within German academia. Perhaps, similar to those who came before me and tried to talk about the lived realities of Black-Germans, multi-ethnic queers, German-Jews, and Turkish, Middle Eastern, and Muslim life in ways that account for majoritarian norms, values, and sensibilities, I have to accept that in this position I am inevitably an outsider. I am afraid no election will change that, as long as political majorities are keen on producing national majorities without reflecting on the legal, economic, and political strategies and techniques that contribute to the naturalization of social inequalities and make it impossible for some to break out of the minority position.

Further reading

Akin, Fatih, Hark Bohm, Rainer Klausmann, Josh Homme, Tamo Kunz, Katrin Aschendorf, Diane Kruger, Denis Moschitto, Johannes Krisch, and Ulrich Tukur. 2018. Aus dem Nichts (Eng.: In the Fade).

Amir-Moazami, Schirin. 2011. “Dialogue as a Governmental Technique: Managing Gendered Islam in Germany.” Feminist Review 98 (1): 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2011.8.

Aydin, Cemil. 2019. The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History. Reprint edition. Harvard University Press.

Borneman, John. 1992. Belonging in the Two Berlins: Kin, State, Nation. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Wendy. 2017. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Reprint edition. New York: Zone Books.

Chin, Rita. 2007. The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany. Cambridge University Press.

Çil, Nevim. 2007. Topographie des Aussenseiters. Verlag Hans Schiler.

Demir, Mustafa and Ergün Sönmez. 1999. “Ausländische” Kinder. Ihre Erziehungs- und Integrationsmisere. Berlin: VWB.

El-Tayeb, Fatima. 2016. Undeutsch: Die Konstruktion des Anderen in der postmigrantischen Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Foroutan, Naika, and Jana Hensel. 2020. Die Gesellschaft der Anderen. Aufbau Verlag-Berlin.

Göktürk, Deniz, David Gramling, and Anton Kaes. 2007. Germany in Transit: Nation and Migration, 1955-2005. 1st ed. University of California Press.

Korteweg, Anna C. 2017. “The Failures of ‘Immigrant Integration’: The Gendered Racialized Production of Non-Belonging.” Migration Studies 5 (3): 428–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx025.

Mandel, Ruth. 2008. Cosmopolitan Anxieties: Turkish Challenges to Citizenship and Belonging in Germany. Duke University Press.

Meier-Braun, Karl-Heinz. 2002. Deutschland, Einwanderungsland. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Partridge, Damani J. 2012. Hypersexuality and Headscarves: Race, Sex, and Citizenship in the New Germany. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Press.

Schiffauer, Werner. 2006. “Enemies within the Gates. The Debate about the Citizenship of Muslims in Germany.” In Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach, edited by Anna Triandafyllidou, Ricard Zapata-Barrero, and Tariq Modood. Routledge.

Schminke, Imke, and Jasmin Siri, eds. 2013. NSU-Terror: Ermittlungen am rechten Abgrund. Ereignis, Kontexte, Diskurse. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Shooman, Yasemin. 2014. »… weil ihre Kultur so ist«: Narrative des antimuslimischen Rassismus. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Shoshan, Nitzan. 2016. The Management of Hate: Nation, Affect, and the Governance of Right-Wing Extremism in Germany. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691171951.001.0001.

Slobodian, Quinn. 2018. “Germany’s 1968 and Its Enemies.” The American Historical Review 123 (3): 749–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/123.3.749.

Van Wyck, Brian. 2017. “Guest Workers in the School?” Geschichte Und Gesellschaft 43 (3): 466–91. https://doi.org/10.13109/gege.2017.43.3.466.

Voigt, Jutta. 2017. Geschmack des Ostens Vom Essen, Trinken und Leben in der DDR. Aufbau Verlag Berlin.

Yasemin Yildiz. 2011. Beyond the Mother Tongue: The Postmonolingual Condition. Fordham University Press.