On October 2, 2016, Colombians were asked to endorse or reject a proposed peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (FARC–EP) guerrilla group. Though the peace agreement would not redress the country’s rampant poverty and economic inequality (Colombia is the second-most unequal country in Latin America), nor would it bring a sudden end to armed conflict (many guerrillas and paramilitary groups are still active, like the National Liberation Army (ELN)), it did contain several bright spots: it would bring peace to a considerable portion of the countryside; it would return land illegally seized during the conflict; it promised to subsidize economic losses incurred by the replacement of illegal albeit extremely profitable coca or poppy crops with legal albeit less profitable agricultural activities, by offering credits for land acquisition to the rural population; it opened up the space for the formation and consolidation of social movements, many of which were able to participate directly in the negotiations; it would mean the end of hostilities between the government and the FARC, whose members would undergo a process of socioeconomic reincorporation into civilian life; and it promised recognition, truth, and reparations for the many victims of the country’s war crimes by establishing a new transitional and restorative justice system.

The shockwaves of the referendum still reverberate through much of Colombia’s social and political landscape. What happened on October 2, 2016, determined the country’s future agenda in terms of land distribution, the illegal drug trade, gender relations, transitional justice, political rhetoric, and the demands of the rural population.

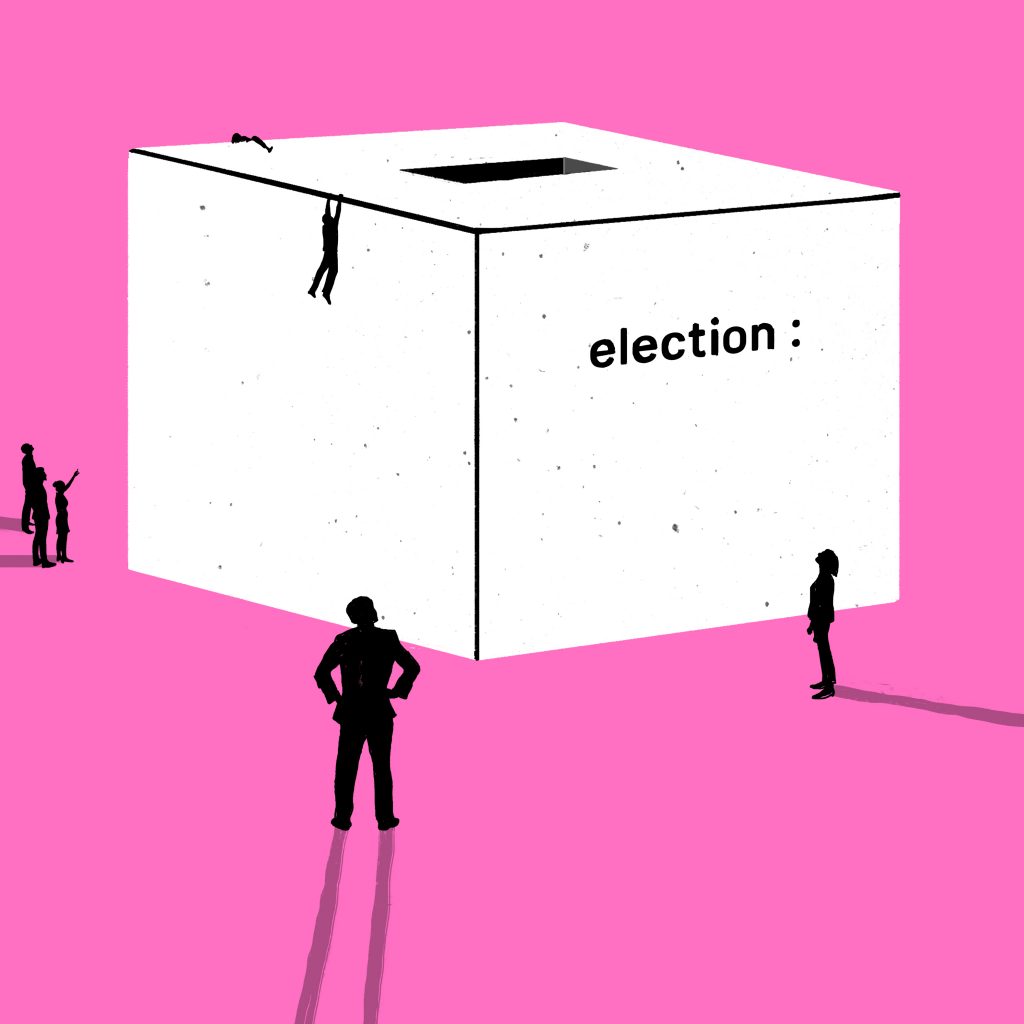

The government called for this popular referendum in order to provide a democratic endorsement mechanism to legitimate the peace process. Public negotiations between the government and the FARC had started back in 2012. At the time, Juan Manuel Santos was the president after winning the 2010 presidential election with former president Alvaro Uribe’s support. Uribe had recently finished serving two consecutive terms (2002-2010), during which time Santos himself had served as Minister of National Defense from 2006-2009. Santos’ decision to engage in talks with the FARC was not met without surprise. When he took office in 2010, his government was expected to continue Uribe’s right-wing political and military agenda, which included not engaging in talks with the FARC. At the heart of Uribe’s presidency was the Democratic Security strategy, a state policy that sought total military victory over rebel groups with a view to restoring perceptions of public safety, safeguarding the interests of landlords and major agribusiness, and bolstering state institutions. This militarized solution was backed by the US, through its $7 billion military aid package initiated in the so-called 2000 Plan Colombia, and a bloc consisting of the far-right, landlords, the military, religious groups, economic elites, and a part of the Colombian people who believed that a peaceful solution to the conflict was untenable after the previous negotiations with the FARC collapsed in 2002. As many have noted, this militarization of Colombia contributed to the rise of paramilitary groups that used violence against community leaders and the organized left. It also led to the extrajudicial killings of, according to some estimates, as many as 10,000 civilians by the military, which framed these victims as guerrilla members to boost the number of combat kills. For all these reasons, Santos’ decision to begin peace negotiations with the FARC and to form alliances with Uribe’s enemies was seen by many as a betrayal.

However, the fact that Santos opposed Uribe’s militarized approach did not entail a shift to the left. Santos—a descendant of one of Colombia’s richest and most influential families—represented a coalition of several parties that embraced neoliberal principles, advocating the need to further open the Colombian economy to global markets and to attract foreign investment. The ruling elite thus certainly had incentives to strike a deal with the FARC: the end of large-scale, rural violence would foster neoliberal development projects, allow for natural resource extraction, and ‘modernize’ the country. Yet the peace agreement between the government and the FARC that was being discussed in Havana (Cuba having been designated a foreign guarantor country at the request of both parties) quickly became not only a promise to cease hostilities but a pluralistic and inclusive forum that incorporated input from a diverse set of voices: from military members to feminist organizations, from LGBT victims to Afro-Colombian and indigenous movements, from Palenquero and Raizal communities to trade-union movements and economic associations.

All in all, the peace agreement was not seen by the people as a providential cure-all that would end the decades-long cycle of violence and repression, yet it was the necessary first step to achieve reconciliation and inclusive development for the most vulnerable Colombians. This explains why Santos convened an extraordinary array of supporters for the agreement: the leaders of the international community, the United Nations, artists, intellectuals, indigenous communities, feminists, students, large business conglomerates, rural social movements, victims’ movements, a sector of the Catholic Church, the LGBTQ community, and Afro-Colombians. In the opposite corner, Uribe and his newly formed party Centro Democrático campaigned against the peace agreement. Uribe grouped together the religious, conservative, and far-right sectors of Colombian society that opposed the accords on religious and political grounds, as well as the large landowners and right-wing paramilitary groups that rejected the land distribution measures for the rural population and ethnic minorities. The Centro Democrático-led No campaign (so-called because it campaigned for saying No to the peace agreement) intentionally misled voters, capitalizing on their fears about the coming of a communist ‘castrochavista’ dictatorship (castrochavista—a sort of portmanteau of [Fidel] Castro and [Hugo] Chávez—refers to the rhetoric appealing to fears that Colombia would become ‘another Venezuela’ or ‘another Cuba’), the dismantling of private property and the patriarchal family, total impunity for war crimes, and the imposition of a ‘gender ideology’ (a distorted and fear-mongering discourse with which religious and far-right leaders preached against the ‘homosexual colonization’ perpetrated by the left and LGBTQ movements). Right-wing groups consistently made use of social media to spread these lies. Despite this pushback, nearly every commentator and poll predicted the victory of the Sí (yes) vote in the 2016 referendum.

24 August 2016 : After more than fifty years of what The New Yorker had termed “the Western Hemisphere’s longest civil war,” the Colombian government and the FARC sign an agreement, sparking the joy of the mainstream press, the international community, and a large portion of Colombian society.

2 October 2016 : The referendum on the peace accords is rejected by a slim majority of voters, with the No campaign winning by a thin margin of just under 0.5% (53,000 votes out of 13,066,025). Notably, there was a low voter turnout rate: 62% of eligible voters did not cast a ballot, that is, more than 20 million people. Moreover, the vote on the referendum showed a deep rural-urban divide. While the country’s peripheral regions (where war hit harder) voted in favor of the deal, the majority of the country’s urban centers (with the exception of Bogotá, Colombia’s capital city) voted against it.

The government used the referendum’s result to address the concerns of many and it quickly drafted a renegotiated accord. The new peace agreement, then, incorporated several changes (in total there were more than 50) related to the most contentious issues of the deal: terms like ‘gender’ and ‘gender identity’ were redacted since they were seen as an attack on religious groups; fears that the army would relinquish its authority to FARC troops were dissipated; it affirmed the right to hold private property, as many were concerned that the agreement would abolish private ownership; it mandated that the FARC would financially contribute to reparations and restitution for victims; it stipulated that the FARC must provide exhaustive and detailed information about their role in drug trade; and it specified the type of penalties to be imposed on former FARC troops. Further, while the first draft of the peace agreement was essentially linked to the constitution very much like an amendment, the new peace agreement was more restricted in terms of its constitutional implications

30 November 2016 : The revised peace agreement is ratified by the Colombian congress. Still, the second agreement did not appease Uribe’s Centro Democrático, who attempted to boycott the legislative votes, but Santos’ allies held a majority in congress. For many, this decision to circumvent another national referendum in favor of parliamentary approval eroded the agreement’s legitimacy since it ultimately overrode the popular will, as expressed (however ambivalently and meagerly) by the referendum.

It is hard to overstate the consequences of the October 2016 referendum. In the following weeks, abundant crowds inundated the country’s main plazas in demonstrations calling for peace. Such a massive mobilization and the resulting climate politicized a large swath of the population, as is evident from the 2019–2020 protests, where many protested in favor of the full implementation of the original peace agreement. In the long run, the referendum shaped political rhetoric, above all in the far-right’s discourse on gender (the term is now used pejoratively by the far-right to attack the left), land distribution, immigration, and nationalism. It also paved the way for Iván Duque’s win in the 2018 presidential election. Duque was the candidate of Uribe’s Centro Democrático party, thus revealing the extent to which Uribe strengthened his political influence after the plebiscite. Currently, the peace agreement is in the process of being implemented, yet the government appears to have little interest in fulfilling its terms, as evinced by the killings of social leaders, the underfunding of programs for rural development, and the constant attacks on the JEP, or Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, the Colombian transitional justice mechanism.