On October 2, 2016, Colombians were asked to endorse or reject a proposed peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (FARC–EP) guerrilla group. Though the peace agreement would not redress the country’s rampant poverty and economic inequality (Colombia is the second-most unequal country in Latin America), nor would it bring a sudden end to armed conflict (many guerrillas and paramilitary groups are still active, like the National Liberation Army (ELN)), it did contain several bright spots: it would bring peace to a considerable portion of the countryside; it would return land illegally seized during the conflict; it promised to subsidize economic losses incurred by the replacement of illegal albeit extremely profitable coca or poppy crops with legal albeit less profitable agricultural activities, by offering credits for land acquisition to the rural population; it opened up the space for the formation and consolidation of social movements, many of which were able to participate directly in the negotiations; it would mean the end of hostilities between the government and the FARC, whose members would undergo a process of socioeconomic reincorporation into civilian life; and it promised recognition, truth, and reparations for the many victims of the country’s war crimes by establishing a new transitional and restorative justice system.

The shockwaves of the referendum still reverberate through much of Colombia’s social and political landscape. What happened on October 2, 2016, determined the country’s future agenda in terms of land distribution, the illegal drug trade, gender relations, transitional justice, political rhetoric, and the demands of the rural population.

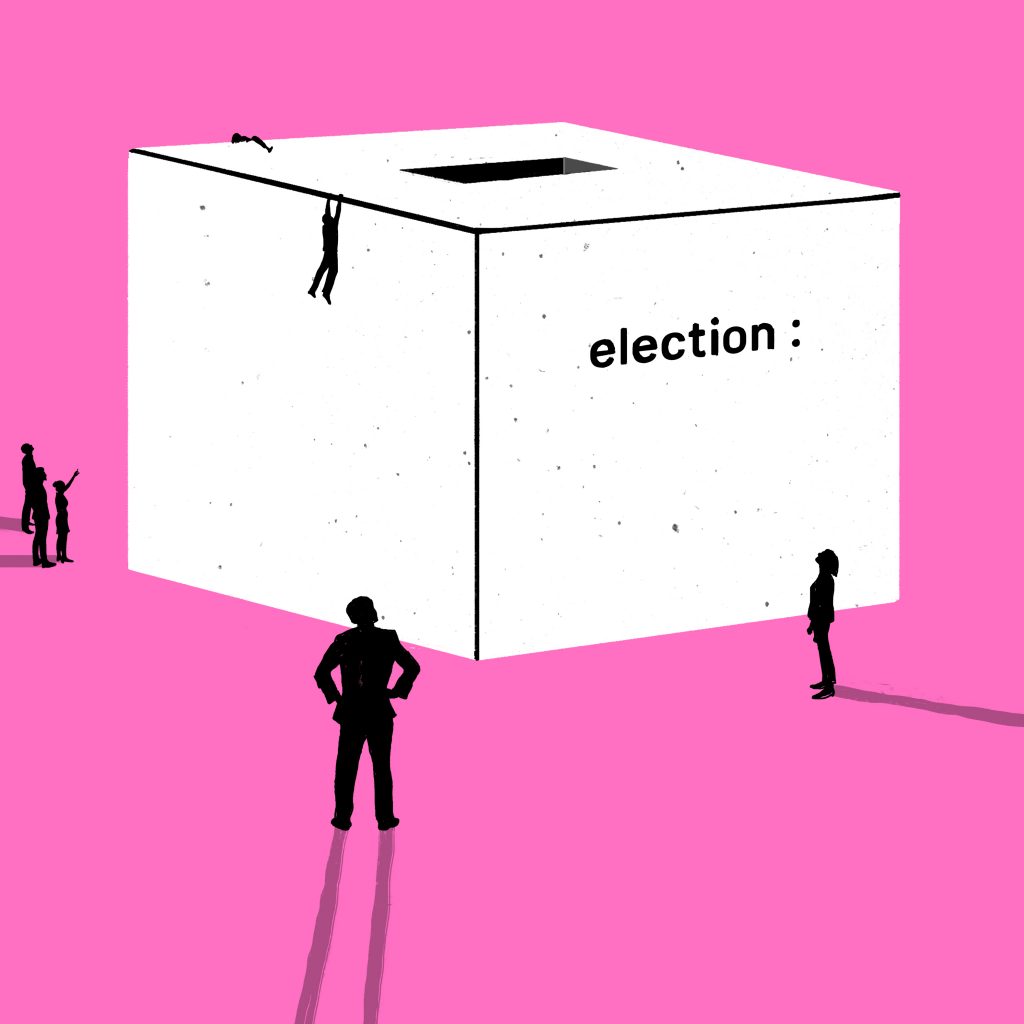

Continue reading “referendum : colombian peace agreement 2016”