Barricade stands in solidarity with the people of Russia and Ukraine who have become unwitting victims of a totally indefensible war initiated by Russian president Vladimir Putin and his oligarchic administration, a crisis that has, in a matter of weeks, led to the displacement of millions of ordinary citizens, driven Europe to the brink of another major refugee crisis, and resulted in thousands of military and civilian casualties. Putin’s attack—alongside his refusal to acknowledge Ukraine as a legitimate state with a democratically elected government—is not just territorial but ethnic and is fueled by a misplaced nostalgia about a purportedly glorious Soviet past. We at Barricade condemn this invasion of a sovereign state by a foreign dictator that has resulted in the destruction of thousands of human lives and livelihoods.

But even as we denounce Putin’s war on Ukraine and his escalating rhetoric around nuclear weapons, we also want to call out the double standards of the United States and mainstream Western media for their convenient elision of the West’s own complicity in the crisis, especially its involvement in NATO’s capital-driven expansionist policies. We express our solidarity for the working people of both countries and mark our protest not only against the war initiated by Putin but also the global neoliberal network founded on an economy of extraction and the maximization of profits. We believe that a war is inseparable from the way we tell the story of the war, and that the US’ (justified) denunciation of Putin also serves to conceal the equally egregious sovereign-territorial invasions the US has made this century, notably in Iraq and Afghanistan in the guise of a “war on terror,” but in erstwhile Yugoslavia as well in 1999 in total disregard of the UN Charter. The current crisis should, therefore, not make us forget the fact that the US and its allies have on several occasions used force to invade and interfere in the internal affairs of other nations, undermined their territorial independence, and brought about regime changes to suit its own geopolitical needs—and that the effects of these actions reverberate and are amplified in hardly unforeseeable dimensions, causing more death, impoverishment, despair, and further conflict, long after such “operations” are “accomplished.”

Excursus on the artist and his art

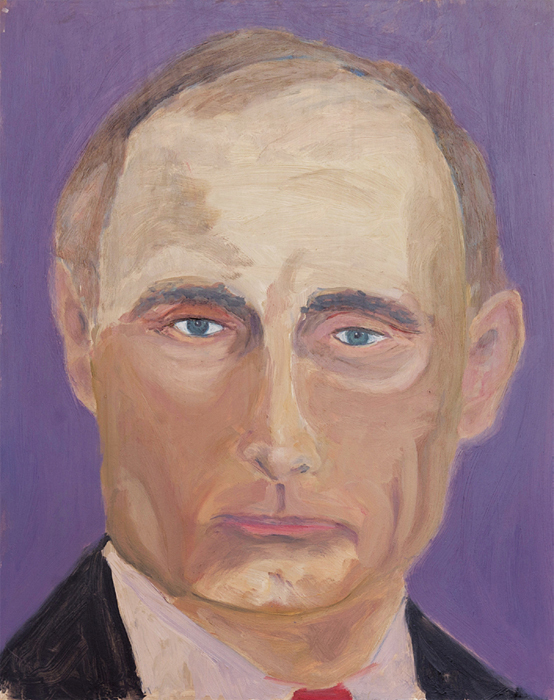

To illustrate the risk of the ease with which US imperial war crimes can be and have been elided or painted over by emerging geopolitical crises—not to mention by our national desire to obfuscate and forget—former president George W. Bush has gifted us a remarkable example. Since retiring from political life, Bush has—like another wartime leader before him, Winston Churchill—taken up painting. Unlike Churchill, who waxed romantic in a famous essay on the pleasures of plein air painting, Bush’s paintings are primarily portraits. Yet not unlike Churchill, whose essay explicitly analogizes the (ostensibly) purposeless activity of art-making with the (overtly) purposive activity of war-making, Bush’s paintings serve an implicit political function. Adam Taylor of the Washington Post wrote in 2014 of Bush’s portrait of Putin: “it is a really good painting aesthetically.” While it’s tempting to sneer at a foreign policy reporter’s aesthetic judgments—and tempting, but less so, to recall that “Hitler was actually a kinda good artist”—what’s more telling is that this comment is smuggled in between parentheses. For this is how revision and rehabilitation of the narrative begins. Matt Saunders, writing also in 2014, but for Artforum—a venue in which one might reasonably expect to encounter credible aesthetic judgments—describes a certain “haplessness” in the painter’s hand: “he moves the paint with carefree gumption.” And yet, Saunders foregoes the opportunity to analogize Bush’s hapless way of moving paint with his hapless art of war or with his carefree gumption in Guantanamo, Iraq, Afghanistan, prompting instead: “The ex-president defines himself as a painter, but do we define him as an artist?” We at Barricade would like to suggest that the portrait is very often just as much of the artist as it is of the sitter.