Protests Commemorating Hanau Massacres in Berlin

by Deren Ertas

On February 20, 2021, Berliners came together in one of the busiest streets of Neukölln, which is home to a community of migrants hailing from all over the world, but especially migrants from the Middle East and North Africa. Organized by several leftist, anti-fascist, and anti-racist syndicates, people from a range of positionalities came together to publicly remember the nine victims of a far-right extremist attack on two shisha bars in the city of Hanau that took place one year ago on February 19. Long forgotten by mainstream German media, demonstrators marched through the district repeating the names of those killed—Hamza Kurtović, Kaloyan Velkov, Mercedes Kierpacz, Fatih Saraçoğlu, Sedat Gürbüz, Vili Viorel Păun, Ferhat Unvar, Gökhan Gültekin, Said Nesar Hashemi—with righteous anger and intention. In a beautiful speech read in German, English, Arabic, and Turkish, they pronounced the structural nature of the violence against those identified as refugees, migrants, and immigrants in Europe against a dominant narrative that dismisses the Hanau massacre as an Einzelfall, or an isolated incident.

“Widerstand überall! Hanau war kein Einzelfall!”

“Resistance everywhere! Hanau was not an isolated incident!”

When I first moved to Berlin-Neukölln in June 2020, there were a series of arson attacks against cars and restaurants owned by migrant families and known anti-fascist activists. The nearby areas were stickered with neo-Nazi insignia. The Left Party MP from Neukölln, Anne Helm, received death threats from an organization that calls itself the National Socialist Underground. She is only one of many activists and migrants who have received death threats or were attacked by right-wing groups. According to a recent data science project, between 2016 and 2020, there have been over 400 hate crimes committed against non-white people in Neukölln alone. As their map shows, the district located in Berlin’s South is a systematic target of racist hate crimes, a fact stubbornly refused to be acknowledged by the German public who continuously fabulates Neukölln as the epicenter of ‘Ausländerkriminalität,’ or ‘foreigner criminality.’

The recent revelations regarding the presence of white supremacist and far-right extremist organizations within Berlin’s rank and file have brought national attention on the issue. Given these proclivities, it perhaps comes as no surprise that right-wing attacks and hate crimes are not investigated and prosecuted in the same way as “gang-related violence” from within non-white communities of Germany’s metropoles.

When the tables are turned—for instance if we speak of the tragic murder of French middle school teacher Samuel Paty by beheading in the hands of an extremist—the response is quite different and almost always involves a condemnation of communities of faith or ethnic belonging. More often than not, the sets of policies that made it possible for them to live in Western Europe or the United States come under revision. In the last months, this has gotten so ridiculous that Emmanuel Macron has an Orbán-esque witch hunt of French academia, which he accuses of being too much under the influence of ‘Islamo-leftist ideas.’

While violence within migrational communities is seen as emanating from non-white proclivities towards criminality, right-wing hate crimes continue to be perceived as isolated events. The structure of white supremacy has its imprint all over the tragic death of the nine people killed in Hanau. The police frequently raid hookah bars, randomly pull over cars driven by black and brown men, and keep spätis (Berlin corner stores mostly run by non-white communities) under constant surveillance. The criminalization of black and brown bodies, as the consequences of this arbitrary regulation makes abundantly clear, sets the foundation for their gruesome murder.

“Yallah, yallah, Antifascista!”

We are marching, few ten-thousands strong, on Sonnenallee, where the shopkeepers, restaurant owners, and residents are overwhelmingly Arab. The same speech that we heard in German, Turkish, and English earlier begins to be read in Arabic. Once the speech is over, we march along the street to the song Ben Haana Wa Maana by DAM. At some point, we come to a halt, and the megaphone is passed around for people to shout slogans or to speak words of solidarity or to share their experiences with racialized violence in Germany. Once the megaphone is in their hands, a young Arab man starts to dance, singing: “Yallah, yallah, antifascista!” and the crowd repeats it. I’m carrying a banner, with my hips swaying to the melody being imparting on the otherwise standard protest cheer. He motions the crowd to get quieter and quieter and progressively take a seat. The slogan can hardly be heard in a whisper when the whole crowd jumps up and once again begins to yell, “Yallah, yallah antifascista!”

— “Ein Hoch auf die Internationale Solidarität!”

– “Cheers to International Solidarity!”

The German anti-fascist movement has an internationalist outlook that was reflected in these two slogans that garnered significant attention and praise during the Hanau protests. Internationalism is central to any movement that tries to fight fascism, a political phenomenon observable across the world. Translation plays an important, if not vital, role in fighting fascism.

This is no less true in Germany, and in Berlin. Neukölln, as I stated above, is a multi-cultural neighborhood with a large Kurdish, Turkish, and Arab population. Working class Germans reside further south in the district. Young Germans and Americans are also moving there as a result of Berlin’s gentrification in the past three decades. The main center of Middle Eastern life was once the more central district of Kreuzberg, but this area was victim to rising rents and ensuing gentrification far earlier after the reunification. Despite the threats to securing a livelihood here in Neukölln, its streets are undeniably multilingual. So much so that I speak as much Arabic and Turkish on a day as I do English or fumble around in my elementary German.

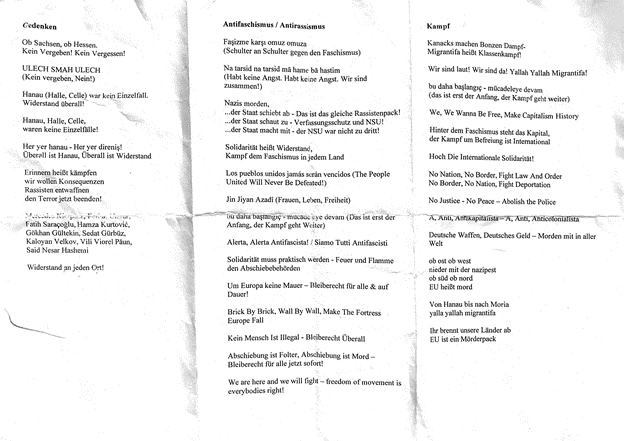

The plurality of languages within the communities most affected by far-right violence is reflected in the wide ranging, polyglot vocabulary of antifascist protests. At the beginning of the Hanau march, protest organizers handed out a half sheet of paper where certain slogans were printed in different languages.

While the absence of Arabic texts is noticeable, one can see the trials of a movement to incorporate many linguistic positions, to break down the nativist monopoly on language, to speak out in a multitude of anti-fascist vocabularies.